Scraping a real website

Last updated on 2025-06-10 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I get the data and information from a real website?

- How can I start automating my web scraping tasks?

Objectives

- Use the

requestspackage to retrieve the HTML content of a website. - Navigate the tree structure behind an HTML document to extract the information we need.

- Understand how to avoid being blocked after sending too many requests.

It’s now time to extract information from an actual website: https://carpentries.org. We’ll focus on retrieving data about upcoming and past workshops taught by The Carpentries global community.

To give you a sense of how web scraping can be useful here, we might use this data to analyze which countries have hosted the most workshops, build a live dashboard showing recent trends in instruction, or even create an app that notifies us when a new workshop is scheduled in our region.

With the basic tools shown here, you can build similar apps and analyses using the website(s) you’re interested in. But always keep in mind the code of conduct from the previous episode, especially the first point: there might be an easier and more appropriate way to access the data you need.

In fact, for the example we’re about to explore, The Carpentries provides a list of data feeds that you can use to access information about upcoming and past workshops directly.

“Requests” the website HTML

In the previous episode we used a simple HTML document, not an actual

website. Now that we’re moving into a more realistic and complex

scenario, we’ll add another tool to our toolbox: the

requests package.

For this lesson, we’ll use requests solely to retrieve

the HTML content of a website. Keep in mind that requests

offers much more functionality, which you can explore in the Requests package

documentation.

We’ll be scraping The Carpentries website, specifically the pages

listing upcoming

and past workshops](https://carpentries.org/workshops/past-workshops/). To

do that, we’ll first load the requests package and then use the

.get(url) function and the .text property to

fetch and store the HTML content of the page.

Additionally, to simplify our navigation through the HTML document,

we’ll use the Regular

Expressions module re to remove all newline characters

(\n) and their surrounding whitespace. You can think of

this as a pre-processing or cleaning step. While we won’t go into detail

here, you can explore more about the topic in this by Library

Carpentry Introduction to Regular Expressions.

PYTHON

# Loading libraries

import requests

import re

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from time import sleep

import pandas as pd

from tqdm import tqdm

# Getting the HTML from our desired URL as a text string

url = 'https://carpentries.org/workshops/upcoming-workshops/'

req = requests.get(url).text

# Cleaning and printing the string

cleaned_req = re.sub(r'\s*\n\s*', '', req).strip()

print(cleaned_req[0:1000])OUTPUT

<!doctype html><html class=scroll-smooth lang=en-us dir=ltr><head><meta charset=utf-8><meta name=viewport content="width=device-width"><title>Upcoming workshops | The Carpentries</title><link rel=preconnect href=https://fonts.googleapis.com><link rel=preconnect href=https://fonts.gstatic.com crossorigin><link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Mulish:ital,wght@0,200..1000;1,200..1000&display=swap" rel=stylesheet><script defer src=https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/@glidejs/glide@3.5.x></script><script src=https://kit.fontawesome.com/3a6fac633d.js crossorigin=anonymous></script><link rel=stylesheet href=https://cdn.datatables.net/1.13.6/css/jquery.dataTables.min.css><script src=https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.7.1.min.js></script><script src=https://cdn.datatables.net/1.13.6/js/jquery.dataTables.min.js></script><script src=https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/moment@2.29.1/moment.min.js></script><script src=https://cdn.datatables.net/plug-ins/1.13.6/sorting/datetime-moment.js></script><scWe truncated the output to show only the first 1000 characters of the

document, as it’s too long to display fully. Still, we can confirm it’s

HTML and notice some elements that weren’t present in the earlier

example, such as <meta>, <link>

and <script> tags.

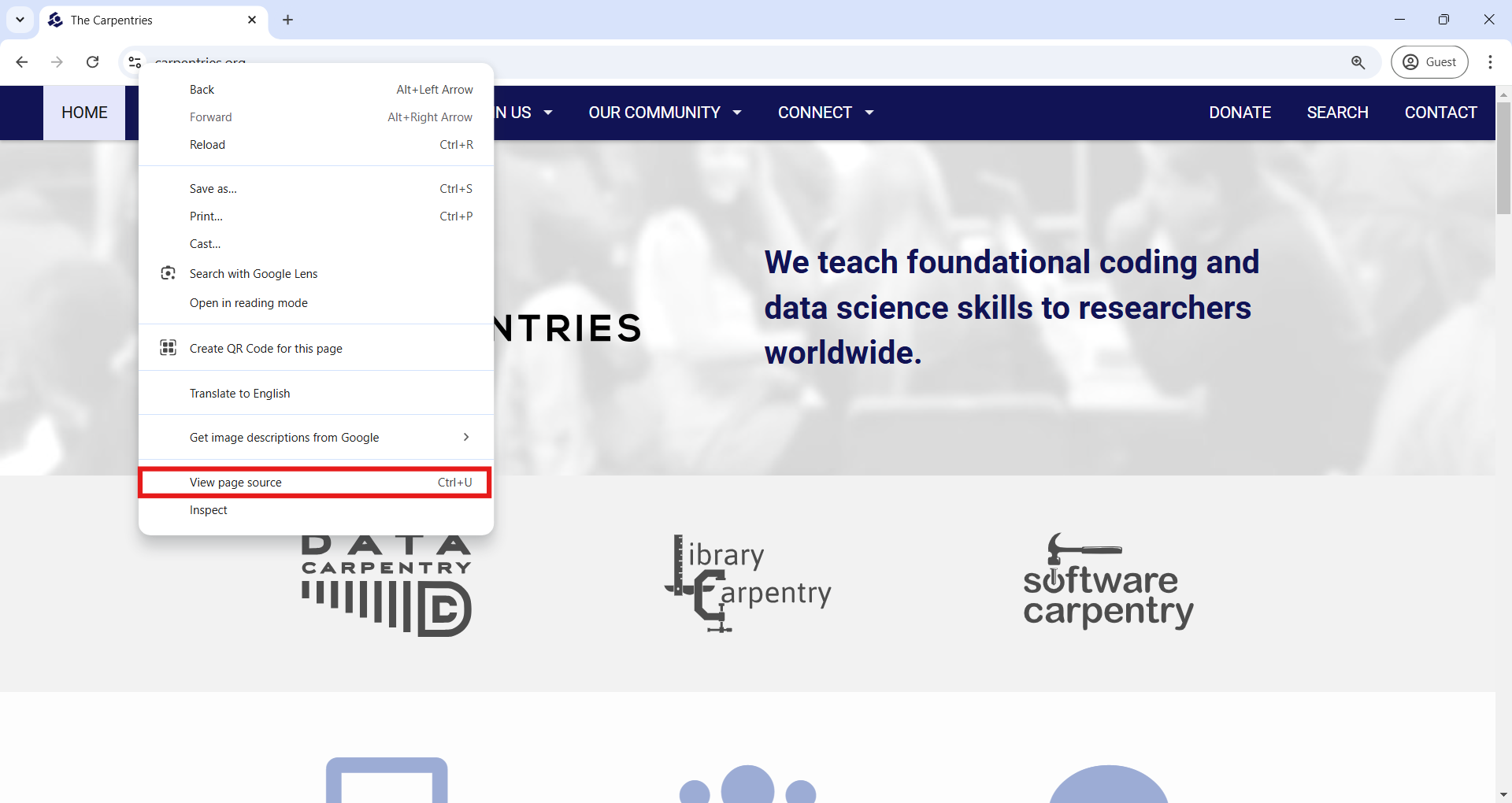

There’s also another way to view the HTML behind a website directly in your web browser. In Google Chrome, you can right-click anywhere on the page (on a Mac, hold the Control key while clicking), then choose “View page source” from the pop-up menu, as shown in the next image. If you don’t see that option, try clicking elsewhere on the page. A new tab will open showing the full HTML document for the site you were viewing.

In the HTML page source in your browser, you can scroll down to find

the first-level header (<h1>) with the text “Upcoming

workshops.” An easier way is to use the Find bar (press Ctrl + F on

Windows or Command + F on Mac) and search for “Upcoming workshops.”

From that point, you can read the surrounding HTML and compare it to

how the content appears on the rendered website. You’ll see how

formatting is handled through tags like unordered lists

(<ul>), list items (<li>),

paragraphs (<p>), and content divisions

(<div>).

Finding the information we want

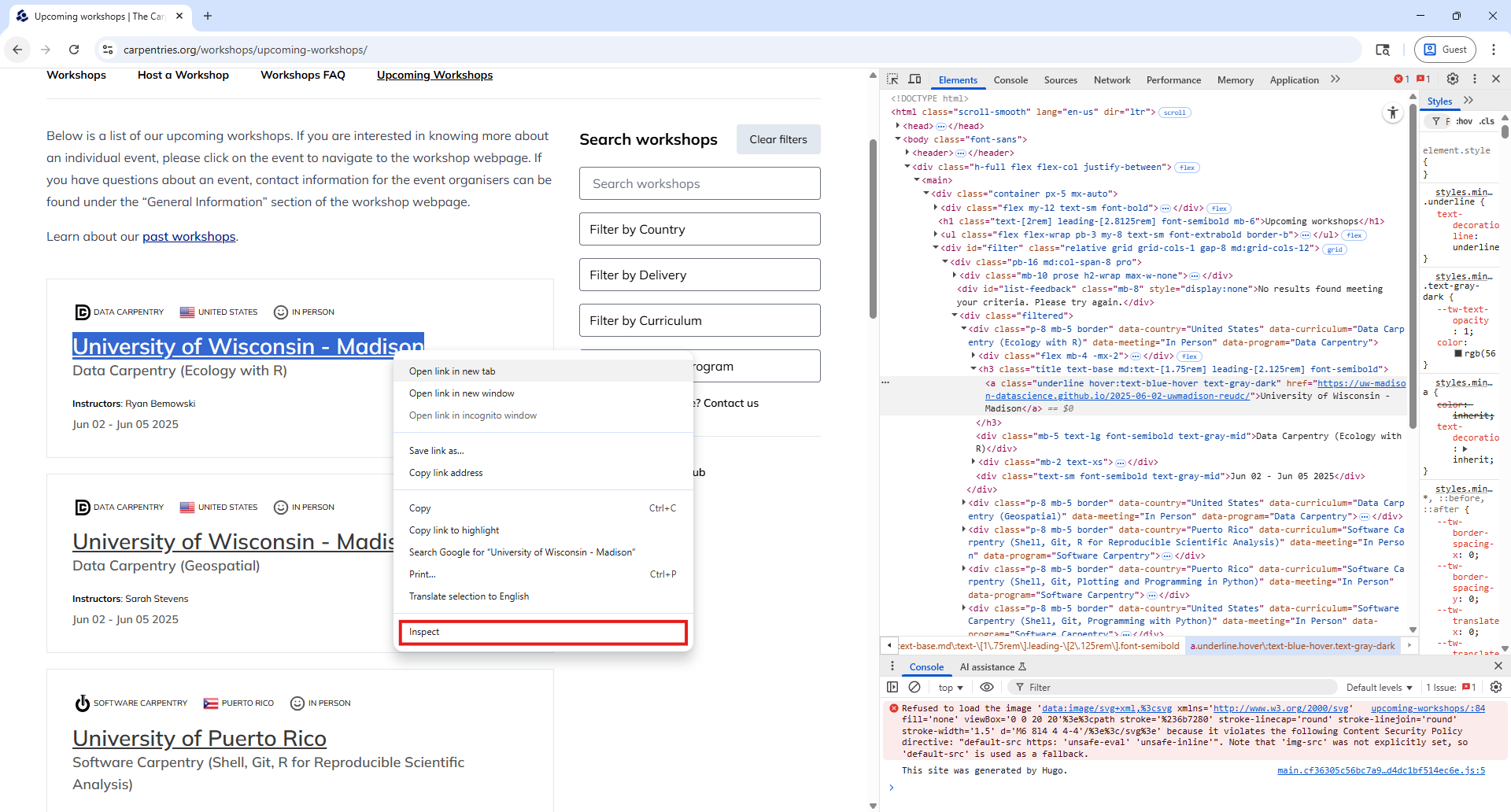

However, carefully reading the entire HTML document to understand its structure and locate the workshop data would be time-consuming. Fortunately, modern web browsers offer a helpful tool called “Inspect”. With this tool, you can examine the specific HTML behind any element on a webpage.

To use it, right-click on the element you’re interested in (or hold the Control key and click, if you’re on a Mac), and then select “Inspect” from the pop-up menu.

Let’s try this with the first item in the Upcoming Workshops list, as shown in the screenshot below. (Keep in mind that your first listed workshop might differ, since the page is updated frequently.)

Using the Inspect feature opens DevTools on the side of your browser. DevTools offers a suite of tools for inspecting, debugging, and analyzing web pages in real-time. For this workshop, we’ll focus on just one: the “Elements” tab.

If you selected the organization name to inspect (as shown in the

screenshot), you’ll see an anchor (<a>) element

highlighted in the Elements tab. Around it, as its parent, you’ll find a

third-level header marked by <h3> tags. This provides

a visual example of the tree-like structure we discussed earlier,

elements nested inside other elements.

Back in our code, we left off after retrieving the HTML behind the

website using the requests package and storing it in a variable named

req.

Now, we can use the BeautifulSoup() function to parse

that HTML, just like we did before. The code below shows how we create

the soup object and use .find_all() to locate all the

third-level headers (<h3>) in the page.

PYTHON

# Parsing the HTML with BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(cleaned_req, 'html.parser')

# Finding all third-level headers and doing a formatted print

h3_by_tag = soup.find_all('h3')

print("Number of h3 elements found: ", len(h3_by_tag))

for n, h3 in enumerate(h3_by_tag):

print(f"Workshop #{n} - {h3.get_text()}")Besides searching elements by tag, it’s often useful to search using

attributes like id or class. In our case, we can see the h3

elements have a class attribute with multiple values: “title text-base

md:text-[1.75rem] leading-[2.125rem] font-semibold”. This set of classes

is used to apply styling, and it can help us target all elements that

share the same formatting.

So instead of selecting all <h3> tags directly, we

can search for elements with this specific class using the

class_ argument of .find_all(), like this:

PYTHON

# An alternative using the "class" attribute, instead of the h3 tag

h3_by_class = soup.find_all(class_="title text-base md:text-[1.75rem] leading-[2.125rem] font-semibold")This will give us the same elements as before, but demonstrates how to refine your search by class —an especially useful technique when different parts of a webpage use the same tag but serve different purposes.

Extracting data

Let’s go back to our web browser. Using the “Inspect” tool, can you

identify the parent of the first <h3> element?

If you guessed a content division element (a <div>

tag), you’re right! But exactly which <div> among all

those in the HTML? You’ll notice that this parent div

stands out because it has a class attribute attribute with

the value “p-8 mb-5 border”.

The animation below illustrates that all the information for each

workshop is grouped within a <div> element marked by

that same class attribute. It also shows how the “Inspect” tool

highlights the relevant portion of the webpage when you hover over an

HTML element, making it easier to understand the structure and pinpoint

the content you want to extract.

Understanding the tree structure of the HTML will help us navigate it

and extract the information we want. Navigating this tree is also

something we can do with BeautifulSoup. For example, let’s find the

parent of the first <h3> element using the

.parent property. As expected, this will return the

<div> element with the class attribute “p-8 mb-5

border”.

PYTHON

# Get the parent of the first h3 element and prettify it

div_firsth3 = h3_by_class[0].parent

print(div_firsth3.prettify())Remember, the output shown here is probably different than yours, as the website is continuously updated.

OUTPUT

<div class="p-8 mb-5 border" data-country="Puerto Rico" data-curriculum="Software Carpentry (Shell, Git, R for Reproducible Scientific Analysis)" data-meeting="In Person" data-program="Software Carpentry">

<div class="flex mb-4 -mx-2">

<div class="flex items-center mx-2">

<img alt="" class="mx-1" src="/software.svg"/>

<span class="text-[0.625rem] uppercase">

Software Carpentry

</span>

</div>

<div class="flex items-center mx-2">

<img alt="" class="mr-1" height="20" src="/flags/pr.png" width="20"/>

<span class="text-[0.625rem] uppercase">

Puerto Rico

</span>

</div>

<div class="flex items-center mx-2">

<img alt="" class="mx-1" src="/In-Person.svg"/>

<span class="text-[0.625rem] uppercase">

In Person

</span>

</div>

</div>

<h3 class="title text-base md:text-[1.75rem] leading-[2.125rem] font-semibold">

<a class="underline hover:text-blue-hover text-gray-dark" href="https://dept-ccom-uprrp.github.io/2025-06-04-uprrp-r/">

University of Puerto Rico

</a>

</h3>

<div class="mb-5 text-lg font-semibold text-gray-mid">

Software Carpentry (Shell, Git, R for Reproducible Scientific Analysis)

</div>

<div class="mb-2 text-xs">

<strong class="font-bold">

Instructors

</strong>

:

<span class="instructors">

Humberto Ortiz-Zuazaga, Airined Montes Mercado

</span>

</div>

<div class="mb-4 text-xs">

<strong class="font-bold">

Helpers

</strong>

:

<span class="helpers">

Isabel Rivera, Diana Buitrago Escobar, Yabdiel Ramos Valerio

</span>

</div>

<div class="text-sm font-semibold text-gray-mid">

Jun 04 - Jun 10 2025

</div>

</div>Taking a careful look, we can start to detect where the information we want is located and how to extract it in a structured way.

We already know the workshop host organization is inside the

<h3> element, and from there we can also get the

hyperlink to that specific workshop’s website. Within the parent

<div>, we can extract additional details such as the

curriculum, country, format (in-person or online), and program (Software

Carpentry, Data Carpentry, Library Carpentry, The Carpentries).

As shown in the previous episode, we can store all this information in a Python dictionary, which we can later transform into a Pandas DataFrame for easier analysis.

PYTHON

# Create an empty dictionary and fill it with the info we are interested in

dict_workshop = {}

dict_workshop['host'] = div_firsth3.find('h3').get_text()

dict_workshop['link'] = div_firsth3.find('h3').find('a').get('href')

dict_workshop['curriculum'] = div_firsth3.get('data-curriculum')

dict_workshop['country'] = div_firsth3.get('data-country')

dict_workshop['format'] = div_firsth3.get('data-meeting')

dict_workshop['program'] = div_firsth3.get('data-program')Ok, that’s the code for extracting information about the first workshop listed, but what about all other workshops? Loop time!

We’ll use the same logic of the previous code block. But first, we’ll find all elements with the class “p-8 mb-5 border”, which we know are the containers for each workshop.

PYTHON

# Find all divs that match a class attribute

divs = soup.find_all('div', class_="p-8 mb-5 border")

# Create an empty list, and fill it with info on each of the workshops found

workshop_list = []

for item in divs:

dict_workshop = {}

dict_workshop['host'] = item.find('h3').get_text()

dict_workshop['link'] = div_firsth3.find('h3').find('a').get('href')

dict_workshop['curriculum'] = div_firsth3.get('data-curriculum')

dict_workshop['country'] = div_firsth3.get('data-country')

dict_workshop['format'] = div_firsth3.get('data-meeting')

dict_workshop['program'] = div_firsth3.get('data-program')

workshop_list.append(dict_workshop)

# Transform list into a DataFrame

upcomingworkshops_df = pd.DataFrame(workshop_list)Great! We’ve finished our first scraping task on a real website. Be

aware that there are multiple ways of achieving the same result. For

example, instead of finding the div elements with the “p-8

mb-5 border” class attribute, we can find the container of all the

workshops, a div with a class attribute of “filtered”.

Then, we can use a while loop across all its children, each of these

being one workshop container. The rest of the code would be the

same.

PYTHON

# Find the container of all the workshops

container = soup.find('div', class_="filtered")

# Use the .contents property to get all the children, and accessing the first element

child_div = container.contents[0]

workshop_list = []

# Create an empty list, and fill it with info on each of the workshops found

while child_div is not None:

dict_workshop = {}

dict_workshop['host'] = child_div.find('h3').get_text()

dict_workshop['link'] = child_div.find('h3').find('a').get('href')

dict_workshop['curriculum'] = child_div.get('data-curriculum')

dict_workshop['country'] = child_div.get('data-country')

dict_workshop['format'] = child_div.get('data-meeting')

dict_workshop['program'] = child_div.get('data-program')

workshop_list.append(dict_workshop)

# Next iteration of the loop will be with the next sibling

child_div = child_div.next_sibling

# Transform list into a DataFrame

upcomingworkshops_df = pd.DataFrame(workshop_list)

upcomingworkshops_dfA key takeaway from this exercise is that, when we want to scrape data in a structured way, we have to spend some time getting to know how the website is structured and how we can identify and extract only the elements we are interested in.

Challenge

Extract the same information as in the previous exercise, but this time from the Past Workshops Page at https://carpentries.org/past_workshops/. Which 5 countries have held the most workshops, and how many has each held?

We can reuse directly the code we wrote before, changing only the URL we got the HTML from.

PYTHON

# Get HTML and parse it with BeautifulSoup

url_past = 'https://carpentries.org/workshops/past-workshops/'

req_past = requests.get(url_past).text

soup_past = BeautifulSoup(req_past, 'html.parser')

# Find all divs that match a class attribute

divs_past = soup_past.find_all('div', class_="p-8 mb-5 border")

# Create an empty list, and fill it with info on each of the workshops found

workshop_list = []

for item in divs_past:

dict_workshop = {}

dict_workshop['host'] = item.find('h3').get_text()

dict_workshop['link'] = item.find('h3').find('a').get('href')

dict_workshop['curriculum'] = item.get('data-curriculum')

dict_workshop['country'] = item.get('data-country')

dict_workshop['format'] = item.get('data-meeting')

dict_workshop['program'] = item.get('data-program')

workshop_list.append(dict_workshop)

# Transform list into a DataFrame

pastworkshops_df = pd.DataFrame(workshop_list)

print('Total number of workshops in the table: ', len(pastworkshops_df))

print('Top 5 of countries by number of workshops held: \n',

pastworkshops_df['country'].value_counts().head())Challenge

From the same upcoming workshops website, modify the code to also extract the list of instructors, helpers, and the dates of the workshops.

Instructors appear to be inside a span element

identified with the “instructors” class attribute. Similarly for

helpers. Workshop dates are inside a div element, with a

class attribute of value “text-sm font-semibold text-gray-mid”. We only

need to add three lines to our loop, and this is how it would look

like.

PYTHON

for item in divs:

dict_workshop = {}

dict_workshop['host'] = item.find('h3').get_text()

dict_workshop['link'] = item.find('h3').find('a')['href']

dict_workshop['curriculum'] = item.get('data-curriculum')

dict_workshop['country'] = item.get('data-country')

dict_workshop['format'] = item.get('data-meeting')

dict_workshop['program'] = item.get('data-program')

dict_workshop['instructor'] = item.find('span', class_ = "instructors").get_text() if item.find('span', class_ = "instructors") is not None else ''

dict_workshop['helper'] = item.find('span', class_ = "helpers").get_text() if item.find('span', class_ = "helpers") is not None else ''

dict_workshop['date'] = item.find('div', class_ = "text-sm font-semibold text-gray-mid").get_text()

workshop_list.append(dict_workshop)You’ll notice the extra if ... else statements in the

instructor and helper extraction. This avoids the code to show an error

if the instructors or helpers are not listed in the workshop, and

therefore BeautifulSoup can find them in the HTML.

Automating data collection

Until now, we’ve only scraped one website page at a time. However,

sometimes the information you need is spread across multiple pages, or

you may need to follow a trail of hyperlinks. With the tools we’ve

learned so far, handling this task is straightforward. You would simply

add a loop that navigates to each page, fetches the HTML using the

requests package, and parses it with

BeautifulSoup to extract the necessary data.

An important consideration when doing this is to include a wait time between each request to avoid overloading the web server providing the data. Sending too many requests in a short period can disrupt access for other users or even cause the server to crash. If the website detects excessive requests, it might block your IP address to visit the website or, in extreme cases, take legal action.

To prevent this, you can use Python’s built-in time

module and its sleep() function to pause between requests.

The sleep() function makes Python wait for a specified

number of seconds before moving on to the next line of code. For

example, the following code pauses for 10 seconds between each print

statement.

Let’s incorporate this important principle as we extract additional

information from each workshop’s individual website. We already have our

upcomingworkshops_df DataFrame, which includes a

link column containing the URL for each workshop’s webpage.

For example, let’s make a request to retrieve the HTML of the first

workshop in the DataFrame and take a look.

PYTHON

# Get the first link from the upcominworkshops dataframe

first_url = upcomingworkshops_df.loc[0, 'link']

print("URL we are visiting: ", first_url)

# Retrieve the HTML

req = requests.get(first_url).text

cleaned_req = re.sub(r'\s*\n\s*', '', req).strip()

# Parse the HTML

soup = BeautifulSoup(cleaned_req, 'html.parser')If we explore the HTML using the ‘View page source’ or ‘Inspect’

tools in the browser, we notice something interesting inside the

<head> element. Because this information is within

<head> rather than the <body>, it

won’t be displayed directly on the page, but the

<meta> elements provide metadata that helps search

engines better understand, display, and index the page.

Each <meta> tag contain useful information for our

workshop table, for example, such as well-formatted start and end dates,

the exact location with latitude and longitude (for in-person

workshops), the language of instruction, and a structured listing of

instructors and helpers. These data points can be identified by the

“name” attribute of the <meta> tags, with the desired

information stored in their “content” attributes.

The following code automates extracting this data from each

workshop’s website, but only for the first five workshops in our

upcomingworkshops_df DataFrame. We limit it to five to

avoid sending too many requests at once and overwhelming the server,

though we could extend this to all workshops if needed.

PYTHON

# List of URLs in our dataframe

urls = list(upcomingworkshops_df.loc[:5, 'link'])

# Start an empty list to store the different dictionaries with our data

list_of_workshops = []

# Start a loop over each URL

for item in tqdm(urls):

# Get the HTML and parse it

req = requests.get(item).text

cleaned_req = re.sub(r'\s*\n\s*', '', req).strip()

soup = BeautifulSoup(cleaned_req, 'html.parser')

# Start an empty dictionary and fill it with the URL, which

# is our identifier with our other dataframe

dict_w = {}

dict_w['link'] = item

# Use the find function to search for the <meta> tag that

# has each specific 'name' attribute and get the value in the

# 'content' attribute

dict_w['startdate'] = soup.find('meta', attrs = {'name': 'startdate'}).get('content')

dict_w['enddate'] = soup.find('meta', attrs = {'name': 'enddate'}).get('content')

dict_w['language'] = soup.find('meta', attrs = {'name': 'language'}).get('content')

dict_w['latlng'] = soup.find('meta', attrs = {'name': 'latlng'}).get('content')

dict_w['instructor'] = soup.find('meta', attrs = {'name': 'instructor'}).get('content')

dict_w['helper'] = soup.find('meta', attrs = {'name': 'helper'}).get('content')

# Append to our list

list_of_workshops.append(dict_w)

# Be respectful, wait at least 3 seconds before a new request

sleep(3)

extradata_upcoming_df = pd.DataFrame(list_of_workshops)Challenge

It’s possible you encountered an error when running the previous code block. The most likely cause is that the URL you tried to access doesn’t exist. This is known as a 404 error, which means the requested page cannot be found on the web server.

How would you approach handling this kind of error to make your scraping process more robust?

A straightforward Pythonic way to handle errors when accessing URLs is to use a try-except block. This allows you to catch any exceptions that occur when trying to access a URL, ignore the problematic URL, and continue processing the rest.

A cleaner approach is to check the actual HTTP response code returned

by the requests call. A status code of 200 means the

request was successful and the page exists. For any other response code,

you can choose to skip scraping that page and optionally log the code

for review.

Key Points

- Use the requests package with

requests.get('website_url').textto retrieve the HTML content of any website. - In your web browser, you can explore the HTML structure and identify elements of interest using the “View Page Source” and “Inspect” tools.

- An HTML document is a nested tree of elements; navigate it by

accessing an element’s children (

.contents), parent (.parent), and siblings (.next_sibling,.previous_sibling) - To avoid overwhelming a website’s server, add delays between

requests using the

sleep()function from Python’s built-intimemodule.